Long-form – HTTPS and VPNs: How private is your internet browsing?

Web browsing privacy is of increasing concern as people’s business and personal lives become ever more entwined with the internet. This essay examines various connection scenarios to establish how secure your data really is.

Introduction

After years of industry concern, web browsing privacy is finally becoming a matter of interest to the public. There may be several factors behind this, including the Edward Snowden leaks, which revealed the extent to which western governments monitor their citizens’ online activity, and various headline-grabbing data leaks. Although these do not exactly align to web browsing for the most part, there is no doubt they have increased awareness of cyber security and privacy.

Virtual private network (VPN) providers have been quick to capitalise on this, and have entered the public eye so emphatically that NordVPN was even unveiled as the “official cyber security partner” of 2019 Premier League runners-up Liverpool FC. It is not uncommon in the United Kingdom to see dramatic television adverts that imply that hackers can own users instantly if they are not using a VPN. But what exactly does a VPN hide? And how private is your browsing otherwise?

This essay will explore web browsing privacy for users utilising various combinations of a range of technologies, including HTTPS-encrypted connections and VPNs. For each scenario, I will consider what a user’s internet service provider (ISP) and VPN provider can see, as well as the owners of the websites visited and any malicious actors monitoring traffic crossing the network.

Assumptions

In order to focus on the issue of web browsing privacy, it is necessary to make a few assumptions about our theoretical hosts sending and receiving the internet traffic.

Firstly, I will assume that the user’s endpoint is not compromised. If a malicious actor has successfully installed malware on a user’s machine, no number of network protections will ensure their privacy. The hacker may be able to record the user’s keystrokes, record which URLs they visit, take screenshots, and retrieve files, usernames, passwords, and other data from the computer.

I will also assume that the various service providers involved have not been compromised. If a cyber criminal has “owned” the user’s ISP or VPN provider then they would be able to access all the data visible to those organisations. This essay will detail what data those corporations can see – just assume that if they were compromised then the attackers would see the same.

Lastly, there’s the matter of the website the user is browsing to, which again I will assume is secure. There are several factors at play here, including the webmaster’s backend security and the user’s choice of password and/or multi-factor authentication if it is a web service with an account. It is safe to say that if the website is compromised then the user’s browsing activity and any data sent to the site (e.g. information entered in forms) will be visible to the attacker.

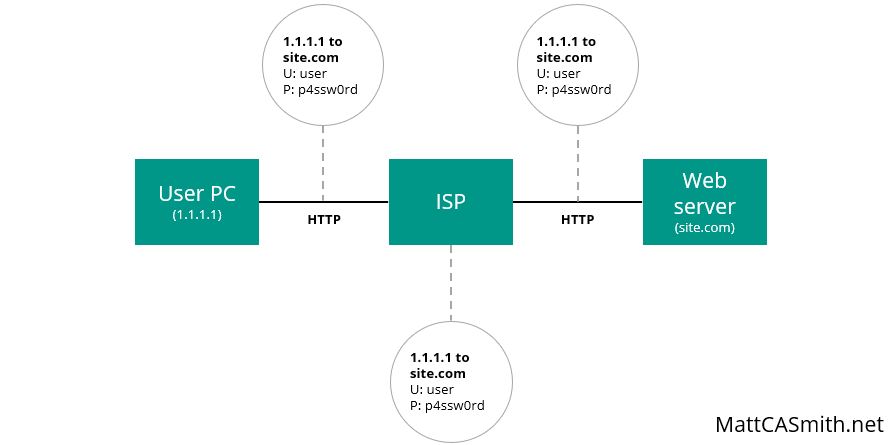

HTTP browsing

Until recent years, the internet was solely reliant on the HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP). While most websites have now switched to the encrypted version – HyperText Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) – some less vigilant webmasters are still serving pages via HTTP. The issue here is that as HTTP is not encrypted, anybody in the middle can see all the browsing data, which is why most modern web browsers flag HTTP connections with a warning message.

This means the ISP can see exactly which page was requested by the user, as well as any additional information they enter – for instance via forms. While it is unlikely that an ISP will actively monitor this data (at least in the UK), HTTP also leaves it open to other observers on its route to the web server.

The real concern here is that any attacker sniffing traffic (i.e. collecting and reading the packets of data sent over the network) can also see everything. This raises privacy concerns if, for example, they can see what Google searches were made or which Facebook profiles were visited, but it can also be disastrous for security – as the attacker can see all data sent over HTTP, this means they can collect any usernames and passwords entered and use them to access or hijack the user’s accounts.

As such, HTTP should be avoided at all costs. Luckily, in 2020 nearly all mainstream websites and apps used in the western world – Google, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, for example – have moved to HTTPS, which encrypts web traffic. Those that have not (and they are surprisingly common outside of the English language internet, at least based on my experience) should be avoided.

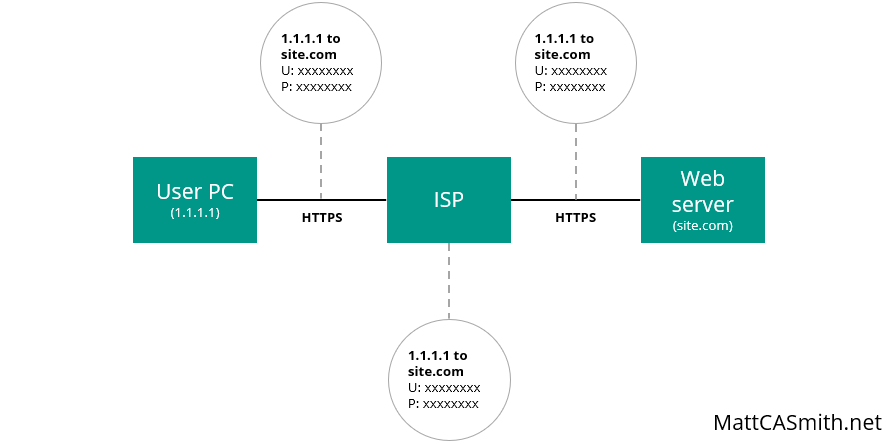

HTTPS browsing

So what happens if the user accesses a site over HTTPS? In this case, Transport Layer Security (TLS) is used to encrypt the data sent and received to shield it from prying eyes.

A new TLS connection is made with each website the user browses to over HTTPS. When the user’s computer contacts the server, they exchange “hello” messages containing random data. The computer verifies the server’s Secure Socket Layer (SSL) certificate is legitimate and the client sends a premaster secret, encrypted with the public key from the server’s SSL certificate.

The server decrypts the premaster secret using its private key, and both systems generate session keys using the client/server random data and premaster secret. Then both systems send “ready” messages encrypted with this session key, signifying that the handshake is complete and the encrypted connection is ready for use. All data sent from this point is encrypted.

What does that encrypted connection mean for browsing privacy? All data sent between the client and the server is encrypted, meaning it cannot be understood by the user’s ISP or anybody eavesdropping on network traffic. However, it is worth noting that the initial Domain Name Service (DNS) request, which looks up the IP address that corresponds to a domain, will still be in plain text, so the domain visited (e.g. MattCASmith.net) can be picked out and used to track browsing activity.

To combat this, a new system called DNS over HTTPS is being tested. However, this will not necessarily completely hide the site the user is visiting – it will just make it slightly more difficult to decipher. While the domain name in the DNS request will be encrypted and unreadable, third parties monitoring the site content packets sent and received will still be able to see the source and destination IP addresses on each – namely the user’s host and the web server. From there, a reverse DNS lookup can be performed on the server’s IP address to find the associated domain.

So with HTTPS the ISP and anybody listening can see the domain requested but none of the content… and that’s about it. As always, the website itself can see all requests and submissions made to it, but it is clear that HTTPS is a massive step up from HTTP in terms of privacy.

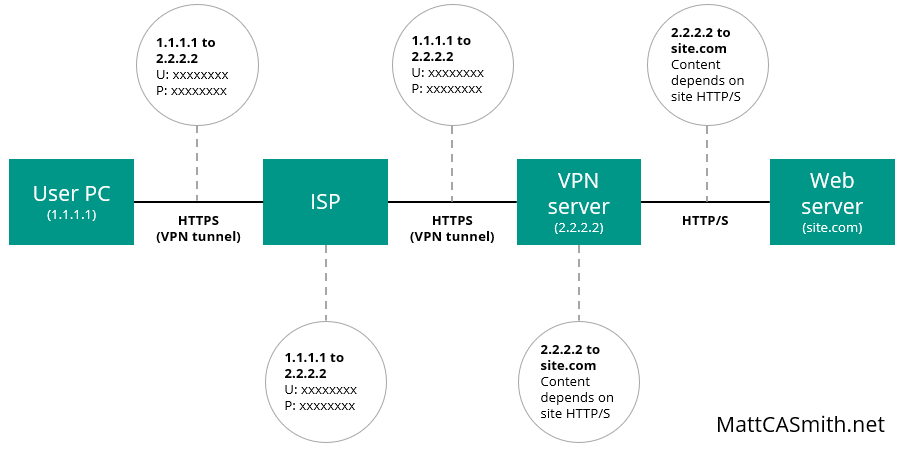

VPN browsing

Next we will take a look at what happens when the user connects via a virtual private network (VPN).

These are the services we discussed earlier, often marketed with vague promises about encryption and security. But what exactly do they do? Essentially, a VPN creates an encrypted tunnel between the user’s computer and the VPN provider’s server. This means all data transmitted between those two points – including DNS requests and content sent over HTTP – is encrypted and cannot be read by the user’s ISP or anybody sniffing packets from the network between these two points.

As connections are made via the VPN server, this also masks the user’s IP address and location from the destination website. This is how some people use VPNs to access Netflix content intended for other nations – if the VPN server is in the Netherlands, for example, then Netflix’s server sees a viewer browsing from that server’s Dutch IP address and returns Dutch content.

However, a VPN still has its limitations and does not provide bulletproof privacy. As always, the website visited will know which pages were requested and can store any information the user enters. Even though it can only see the VPN server’s IP address, the site will know who the user is if they log in or have cookies stored on their computer from previous visits.

It is also worth noting that the protocol used for the final leg of the route – between the VPN server and the web server – depends on whether the web server supports HTTPS. If it does not, this connection will be over HTTP and the usual warnings about packet sniffing apply.

However, the biggest risk with a VPN lies with the VPN provider itself. By using a VPN, a user is essentially transferring their trust from their ISP to the VPN provider, as all of their browsing data passes through its servers. If the VPN provider is untrustworthy or has been breached, then malicious actors could potentially see everything that the user does online (potentially even data sent and received from web servers over HTTPS with a successful man in the middle attack).

Logging is also a consideration. While many VPN providers claim not to keep logs of their users’ browsing activity, it is not always wise to take their word for it, as some users have previously discovered. Not only do some VPN providers – especially the free ones – stand to profit from selling such data to advertisers, they may also be required to hand them over to law enforcement if requested, depending on the country the data is stored in. Be sure to do your research before signing up.

How to keep your web browsing private

So what’s the best approach for users who want to avoid revealing their browsing habits to the world? Browsing over HTTP is certainly a no-no, but there are pros and cons to be weighed up when it comes to choosing between a VPN and good old-fashioned HTTPS (which should still be used wherever possible).

HTTPS encrypts all web content, and while the DNS request domain will be visible, that probably will not be of much concern for the average user as “google.com” or “bbc.co.uk” does not give away much about their activity. However, while the bulk of mainstream sites are up-to-date, some websites still use HTTP connections, which do not offer the same privacy and may pose a potential risk.

A VPN, on the other hand, encrypts all data between the user’s computer and the VPN server, even when communicating with sites over HTTP. However, the user essentially entrusts all of their data to the VPN provider, and choosing a trustworthy one can be tricky. A bad choice (or a successful attack on the provider) could spill all of their secrets to an attacker or law enforcement agency anyway.

And again, it is worth underlining here that none of these technologies protect data sent to a website. The web server will always know which pages the user browsed to and what data they submitted. If a VPN is used then this activity will be logged against the VPN server’s IP address, but at the end of the day user data is at the mercy of the site’s privacy policies and security defences.

In all likelihood, taking basic security precautions and sticking to websites that support HTTPS should provide enough privacy for the typical user. However, if you are likely to be using HTTP (or are simply uncomfortable with your ISP knowing which domains you visit) then a VPN can provide an extra layer of privacy – just make sure you choose one that you can trust. As with many choices in cyber security, it all comes down to your personal risk profile and how much you’re willing to spend.

Photo from Junior Teixeira on Pexels