Python tools for Windows forensics: Microsoft Office recent files

Adding to our growing Python forensics tool for Windows, let’s take a look a any Microsoft Office documents the user has recently opened and when they were first and last opened, and add all of this information to our timeline.

What are Office files and how do they help our investigation?

Microsoft Office needs no introduction – it’s by far the most common productivity software suit out there, and by determining which documents, spreadsheets, and presentations the user opened and when they opened them we can tell a lot about their activity.

Shortcuts to recently opened Office files are stored in the user’s Windows directory under AppData/Roaming/Microsoft/Office/Recent, and these contain timestamp information and the path to the file itself. Our next module for the MCAS Windows Forensic Gatherer will parse this data.

Setting things up

As with our other forensics tool modules, the first step is to build out the correct path.

office_recent_directory = windows_drive + ":\Users\\" + username + "\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Office\Recent\\"

print "Microsoft Office recent files directory is %s." % office_recent_directoryFirst we use the username provided by the analyst to construct the path to the Recent folder, which is stored in he office_recent_directory variable. Then we print this information to the screen to help the analyst with any troubleshooting that is needed later.

Iterating through the shortcuts

Now that we know which directory we need to look in, let’s identify which of the files present are shortcuts to recent Microsoft Office files so we can analyse their metadata.

office_recent_files = os.listdir(office_recent_directory)

for recent_file in office_recent_files:

if recent_file[-3:] == "LNK":

full_path = office_recent_directory + recent_file</pre>First we use os.listdir to list the files within the Recent directory and store this data in the variable office_recent_files. Then we use a for statement to iterate through the files to identify if each one is a .lnk by checking the last few characters of its filename. If it is, we proceed to the parsing stage.

Extracting the creation and modification times

We know the current file is a recent document shortcut, so now we can start extracting useful information. We’ll begin with the creation and modification times. Bear in mind that these timestamps refer to the shortcut, not the Office document. The creation time shows the first time the document was accessed, and the modified time tells us when it was last opened.

creation_time = os.path.getctime(full_path)

creation_time = time.strftime('%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S', time.localtime(creation_time))

modified_time = os.path.getmtime(full_path)

modified_time = time.strftime('%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S', time.localtime(modified_time))</pre>These are retrieved using os.path.getctime and os.path.getmtime respectively using the path to the file, which we stored in full_path earlier. Then we use time.strftime to convert the timestamps to a format that matches our forensic timeline and store them in creation_time and modified_time.

Extracting the Office file’s name and path

Now that we’ve extracted the timestamps, let’s take a look at the original file’s name and path.

shell = win32com.client.Dispatch("WScript.Shell")

shortcut = shell.CreateShortCut(full_path)

file_path = shortcut.Targetpath

filename = file_path.rsplit('\\', 1)[-1]</pre>Here we use the win32com library to parse the file’s metadata. The object shortcut is created using the file’s full path, and then the Targetpath function is used to extract the path to the target file and assign it to the file_path variable. Then we can use rsplit to extract all of the text after the final backslash in he path, which will be the Office document’s filename.

Writing the results to the CSV timeline

Now that we have all the information we need, let’s add it to our CSV forensic timeline. I’ve opted to add two entries here – one for when the Microsoft Office document was first opened and one for when it was last opened – just to avoid any confusion over timestamps and make the timeline easier to read.

office_recent_access_line_1 = creation_time + "," + "File/folder accessed" + "," + filename + "," + file_path + "," + username + "," + "," + creation_time + "," + "," + modified_time + "," + "Microsoft Office recent files" + "," + recent_file + "\n"

office_recent_access_line_2 = modified_time + "," + "File/folder accessed" + "," + filename + "," + file_path + "," + username + "," "," + creation_time + "," + "," + modified_time + "," + "Microsoft Office recent files" + "," + recent_file + "\n"

timeline_csv.write(office_recent_access_line_1)

timeline_csv.write(office_recent_access_line_2)

print "Microsoft Office recent file information gathered."

print ""As with our other modules, the variables containing the file data are combined with the right number of commas to match the CSV file’s columns and written to the timeline. Once all files have been process, a success message is printed to the screen, and we’re finished!

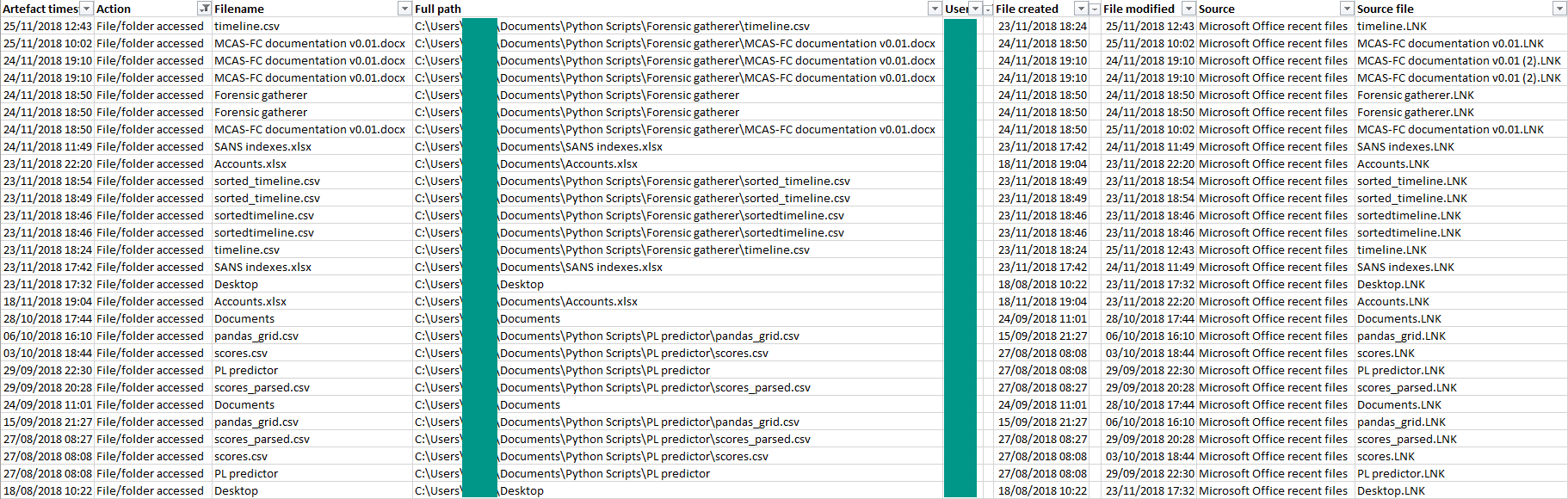

The output

If everything goes to plan, our forensic timeline should have two new lines for each shortcut file in the Microsoft Office recent files folder – one showing the first time each file was opened and one showing the last, each populated with timestamps and information on the original file.

That’s another string added to our bow, and the MCAS Forensics Gatherer can now show which programs a user ran, which files they deleted, when they logged on and off, which pages they viewed in Google Chrome, and which Microsoft Office files they opened and when.

Next month, we’ll take a look at how to tell which pages a user accessed using Mozilla Firefox. Until then, head to the MCAS Windows Forensic Gatherer page if you missed any other posts in the series.

Photo from rawpixel.com on Pexels