Python tools for Windows forensics: Parsing Prefetch program data

Bit by bit, I’m going to build a Python tool to scrape a Windows system disk image for common forensic artefacts and build a CSV timeline from the evidence gathered. In this first post, I’ll parse and add the data stored in Windows Prefetch files.

On my recent SANS course on Windows forensics I learnt about all kinds of forensic artefacts that can be retrieved from Windows systems to determine what the user was doing, which applications they were running, which files they were opening, and much more. All the while, I was wondering whether it would be possible to develop a Python tool to grab common forensic artefacts from a Windows disk image and automatically generate a forensic timeline.

Now things have settled down a bit I’m going to start building one. It would be overwhelming to take on every artefact at once, so I’m going to take a modular approach and build in one artefact at a time, beginning with a relatively easy one: Windows Prefetch file data.

What is Prefetch and how does it help our investigation?

Prefetch is one of the ways Microsoft has attempted to speed up your Windows experience. Basically, when you first run an application, Windows will store data about it in a PF file in the directory C:\Windows\Prefetch. These files’ names will be the executable’s name followed by a dash and a hash of its location – something like CHROME.EXE-CCF9F3F5.pf.

How does this help a forensic investigator? Well, the file created and file modified times of these PF files are set to the times the program was first and last run. Furthermore, multiple files with the same name could indicate that multiple versions of the program have been run, or that identical files were run from different directories on the system.

Setting things up

To successfully parse the information contained in the Prefetch folder, we’ll need to import a few libraries. We’ll get to what exactly each of these is used for a little later.

import os, time, csv, operator

timeline_csv = open("timeline.csv", "a")

windows_drive = raw_input("Enter Windows drive letter: ")

prefetch_directory = windows_drive + ":\Windows\Prefetch\\"

print "Prefetch directory is %s." % prefetch_directoryWe’ll also open a CSV file to save our forensic timeline entries to, and ask the investigator which drive the Windows directory sits on. This means it will be possible to use the tool if a forensic image of a drive is mounted on a non-standard drive letter on a system.

Iterating through .pf files and getting program names

Now we know where the Prefetch folder is, we need to navigate to it, get a list of the files inside, and determine which we’d like to pay attention to based on their extension.

prefetch_files = os.listdir(prefetch_directory)

for pf_file in prefetch_files:

if pf_file[-2:] == "pf":

full_path = prefetch_directory + pf_fileTo achieve this, I’ve used nested conditional statements. First, the os library’s listdir function is used to get a list of files in the Prefetch directory. We then iterate over each file, asking whether the last two characters in its name are “pf”. If that test is successful, we proceed. We also save the file’s full path to the full_path variable. We’ll use this in a moment.

Extracting program name and first and last executed times

It’s time to get the information we need from each Prefetch file – namely the application’s name and the first and last times it was executed on the system.

app_name = pf_file[:-12]

first_executed = os.path.getctime(full_path)

first_executed = time.strftime('%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S', time.localtime(first_executed))

last_executed = os.path.getmtime(full_path)

last_executed = time.strftime('%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S', time.localtime(last_executed))The application name can be retrieved by simply trimming the directory hash from the end of the Prefetch filename. For the first executed time, I used the os library’s getctime function to retrieve the timestamp and then the time library’s strftime function to convert it to a readable format. This process is repeated with getmtime to get the last executed time.

Writing the results to a CSV timeline

To add this information to the forensic timeline we’ll need to create comma-delimited lines to add to a CSV. I’m going to create two entries per file – one for the program’s first execution and one for its most recent – but I’ll include all the available information in each.

first_executed_line = first_executed + "," + app_name + "," + first_executed + "," + last_executed + "," + "Program first executed" + "," + "Prefetch - " + pf_file + "\n"

last_executed_line = last_executed + "," + app_name + "," + first_executed + "," + last_executed + "," + "Program last executed" + "," + "Prefetch - " + pf_file + "\n"

timeline_csv.write(first_executed_line)

timeline_csv.write(last_executed_line)

timeline_csv.close()There’s not much to this other than stringing all of our data together into a single variable with commas between each field, then appending this line to the CSV file. Then we close it.

Sorting the CSV timeline by date and time

A forensic timeline isn’t much use if it’s not in chronological order. Our final step (for now) is to take the data and sort it according to the timestamp in the first column.

with open("timeline.csv") as f:

timeline_csv = csv.reader(f, delimiter=",")

sorted_timeline = sorted(timeline_csv, key=operator.itemgetter(0), reverse=True)

with open("timeline.csv", "wb") as f:

fileWriter = csv.writer(f, delimiter=",")

header_row = "Artefact timestamp", "Filename", "First executed", "Last executed", "Action", "Source"

fileWriter.writerow(header_row)

for row in sorted_timeline:

fileWriter.writerow(row)</pre>There are two elements at play here. First, I reopen the timeline file and use the sorted function to reorder it according to the first column, where the timestamp is stored. Then I use fileWriter to add a header row and overwrite the CSV file with the sorted data.

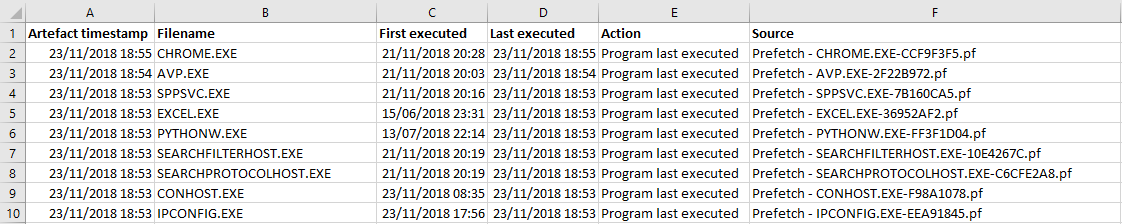

The output

The result is a CSV file that clearly shows the times at which the Prefetch data shows each application ran, whether that’s the first time it was run or the most recent. For my system, this stretches all the way back to when I finished building my PC in June.

Now that the Prefetch data is in our CSV timeline, it’s time to turn our attention to the next type of forensic artefact. I’ll be exploring how to add other Windows artefacts – including those stored in the registry – to the timeline in future posts.

Photo by Mitchell Orr on Unsplash