Enshittified football needs its Steve Jobs moment

“My passion has been to build an enduring company where people were motivated to make great products… The products, not the profits, were the motivation. Sculley flipped these priorities to where the goal was to make money. It’s a subtle difference, but it ends up meaning everything.” – Steve Jobs

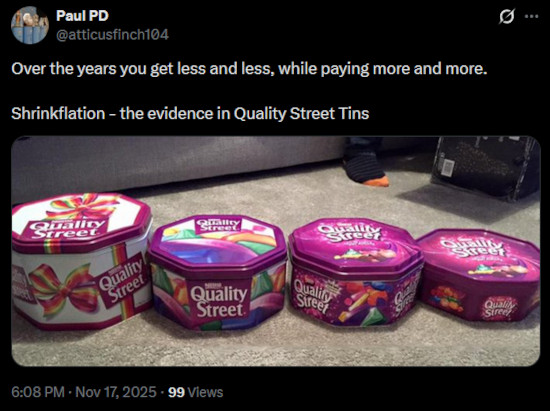

Enshittification has been corroding technology and consumer goods for years. It’s the roadmap where a company makes something good at a reasonable price, but realises it’s sitting on a goldmine if it can squeeze every penny out of the customer. It then destroys the value it provided by jacking up prices, integrating intrusive ads, or simply downgrading the product itself.

Think back to the Facebook of 2007 – you could log on, read a chronological feed of what your friends were up to, and log off. But then Zuckerberg and co realised they had a captive audience, and people couldn’t just leave the site all their friends used. They used that leeway to introduce an algorithmic feed full of posts by pages and businesses, led by those that were either paid for or most likely to evoke a strong emotional response and keep you browsing. Now Facebook is unrecognisable from its fairly wholesome beginnings.

The enshittification trend came for various apps, websites, consumer goods, and even restaurants. But football felt different. Football clubs were rooted in their local communities. Fandom ran in families. And football’s product – the beautiful game itself – was too sacred… until it turned out it wasn’t.

Putting business before football

January saw the unceremonious departure of two Premier League managers under circumstances that made little traditional footballing sense:

-

Enzo Maresca’s Chelsea were on a bad run of form, but he seemed to have his players’ support and some goodwill from Champions League qualification and a summer victory in the Club World Cup.

-

Ruben Amorim’s project secured the backing of the Manchester United board despite a 15th-placed finish in his first season, and his improved team were positioned to fight for a European spot.

The connection? Both were shown the exit after appearing to criticise what they saw as owner interference in footballing affairs. After a disappointing draw at Leeds United, Amorim ranted that he was hired “to be the manager, not to be the coach”, expressing upset over a lack of influence in other areas. Meanwhile, reports emerged that behind the scenes Maresca was frustrated with the club hierarchy for interference in his team selections.

United are yet to appoint a new permanent manager at the time of writing, but Chelsea quickly opted for Liam Rosenior – a relatively inexperienced candidate poached mid-season from Strasbourg, who are also owned by BlueCo. The move has angered both sets of fans – Chelsea’s because of a perceived lack of ambition, and Strasbourg’s because the disruptive move is emblematic of an ownership that prioritises their Premier League sibling.

Chelsea and Manchester United were the two leading English teams in the mid-2000s, battling for domestic and continental trophies on the pitch and competing for the signatures of the world’s best players off it. They regularly won silverware into the mid-2010s. What went wrong? Well, in BlueCo and the Glazer/Ineos partnership respectively, both clubs’ leaders put money before sport, and have brought the enshittification model to football.

The ugly side of the beautiful game

You’ll recall that one of the prerequisites for successful enshittification is a captive audience, and there’s no audience more captive than football fans. In what other sector are consumers bound to a product by local connections, family history, and tribalism? Investors are well aware of this, and know that they can get away with a lot more without their customers going elsewhere.

Despite fan protests since the Glazers took over Manchester United in 2005, the stadium is still full every week. Fans still buy the new shirt and hope that this season will be different. Meanwhile, the team hasn’t won the Premier League or Champions League since 2013, and has seen an endless carousel of managers who receive little long-term backing to implement their vision. Old Trafford has even decayed to the point that the roof leaks when it rains – all while the owners have extracted large sums of money from the club.

Now Chelsea aren’t far behind. When it was purchased in 2022 by BlueCo, a consortium led by Todd Boehly but majority owned by Clearlake Capital, the new ownership introduced itself to fans by cutting a £10 bus subsidy for away games. It then proceeded with a transfer policy that saw it sell a Champions League-winning squad and spend almost £1.5 billion to replace them with mostly young, unproven players. Some observers suspect that rather than building another winning team, the long-term plan is to increase players’ values as much as possible before offloading them for profit.

End of their tether

While first appointee Graham Potter never discovered form in the chaos of BlueCo's early days, the rumour mill would suggest that its transfer strategy may have played a part in the exits of the more promising managers Mauricio Pochettino and Enzo Maresca. Both departures brought murmurings that the managers were unhappy with sales of players they considered core to the squad, or the enforced rotation of players they didn't think were of first-team quality – but only those at the club will know if this is true.

As a fan, there’s little to be done. These clubs are so big, and their brands are so strong, that even if matchgoing supporters attempted a boycott, there are thousands of tourists who would take their places. Supporting another team after decades following their club – not to mention the support of many of their parents and grandparents – isn’t an option. They can only watch the decay under leadership that puts money before the club and its history, and hope for owners who see that football is more than a financial instrument.

A better way

What shines through most clearly in Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs is his commitment to product above all else. Apple became the most valuable company in the world not by penny pinching and cutting spend at all costs, but by building something of such quality that it was a natural success. It wasn’t pure business – design and culture were interwoven.

The investor-owner model at these clubs is short-sighted. It makes money as long as a club can coast on past glories and supporters believe there might be a path to future success, but all that time the foundations are crumbling. Hardcore local fans will support the team no matter what, but continued decline sees the prize money dry up, that lucrative international fan base evaporate, and the value of poorly-performing players plummet.

Owners must recognise that a football club has a connection to local supporters, and that it has a duty to run itself in a sustainable way, with the objective of sporting success above all else.

Like Apple, football needs leaders who care about quality. In football, that means recognising that a club has a connection to local supporters, and that it has a duty to run itself in a sustainable way with the objective of sporting success above all else. Practically, it means investing in a balanced squad, nurturing a good relationship with fans (including reasonable pricing for the working class core), and yes – performing basic stadium maintenance.

Unfortunately, change will require either catastrophe or regulation. The least preferable path forward is that the money dries up. If these clubs decline to a point where the owners are losing money (or the profit isn’t worth the effort), then they may sell up. But that requires once-great clubs to lie in tatters.

The second is regulation along the lines of the German 50+1 rule, whereby club members must retain majority voting rights. This ensures fans’ voices are heard, protecting against high ticket prices, excessive commercialisation, and the prioritisation of profit. It ensures football and its teams remain social and cultural institutions – not just entertainment products – and investors must enter with a similar ethos. They cannot adopt a pure business mindset.

A first step

In England and Wales, the government recently passed the Football Governance Act 2025, which doesn't go as far but does establish an independent regulator and requires support from "a majority of the club’s fans in England and Wales" for changes to major elements like crests and home shirt colours. There are broader clauses aiming to ensure owners' "honesty and integrity", but these look to relate to criminal involvement rather than their intentions for the club.

For now, fans can only hope their club is fortunate enough to have a Jobs-like owner – somebody who understands a subtle difference in motivation makes all the difference. Prioritising either money or a footballing legacy changes everything from the players and managers hired, to fan treatment, to the meetings held day to day. The tone is set at the top, and these motivations make up the soul – or lack thereof – of the clubs many love so fondly.