Endpoint detection and response (EDR) - setting the record straight

When I went to bed on the evening of Friday 19th July, I couldn’t sleep. It was a stuffy summer’s night in London, and the adrenaline was still pumping through my veins after one of the more notable days in recent memory for cyber security. Still, laying awake gave me time to reflect on what I’d seen.

Cyber security is a function that normally runs quietly in the background, so when it does make the headlines, it’s often for the wrong reasons. In the past, we’ve seen huge incidents like NotPetya and Wannacry become global news, but yesterday, it was a security product itself that stole the show.

What exactly happened?

In short: CrowdStrike pushed a bad update to Falcon, a leading endpoint detection and response (EDR) product, that caused a lot of Windows computers to fail to boot. This triggered chaos due to the number of computers around the world running the software. A workaround was quickly discovered, but it needed to be completed manually on each affected system, causing a huge headache for IT administrators.

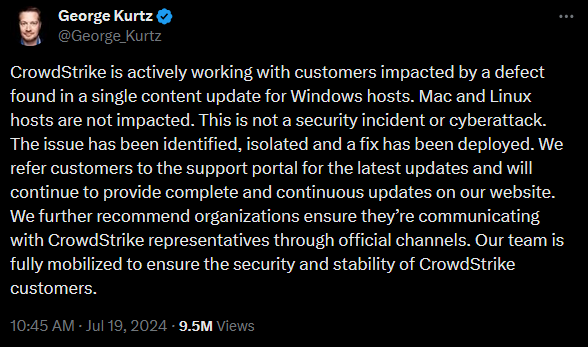

President and CEO George Kurtz took to X to try to reassure the world that no cyber security incident had occurred, and said that CrowdStrike had deployed a fix. He would later share more apologetic posts, including a letter on the firm’s website, but CrowdStrike as a company is not the focus of this post.

Cyber security is a cat and mouse game between those who wish to do harm and those who protect our systems, and for this reason security software needs constant updates to detect and prevent the latest attacker techniques. To effectively monitor endpoints, the software must also run in a privileged state, which means that if it fails, it can easily cause more problems than standard user mode applications.

Therefore, although CrowdStrike will certainly want to go over its internal testing and review processes, it’s important to remember that a similar thing could happen if any other security vendor made a similar mistake (for example, we saw a similar incident on a smaller scale with Symantec in 2019).

Misconceptions and inaccuracies

There are a thousand articles out there about the bug itself, how it was fixed, and what this means for CrowdStrike, so I won’t retread that ground here. After the initial shock of what was happening, the next thing that caught my attention was the way CrowdStrike - and by extension EDR as a whole - was being discussed, which showed a complete lack of understanding of the technology and the entire sector.

The internet is a terrible place to read about things you’re an expert in, but this trend wasn’t limited to the general population on social media. Even on relatively technical forums like Hacker News there was a strange tone to the conversations, and experienced technology journalists at respected publications dropped huge inaccuracies into their writing. Broadly, these misconceptions fell into three categories:

1. “EDR is anti-virus software”

2. “EDR is corporate spyware”

3. “EDR isn’t worth the risk”

I don’t think any of these inaccuracies were spread maliciously. I think they came more from a lack of understanding of what an EDR tool is and does and what cyber security teams are there to do. Therefore, I thought it would be worth writing an article covering the truth behind each of these sentiments.

1. “EDR is anti-virus software”

Since home and office computing became mainstream around the 1990s, the vague security threat of “viruses” has loomed. In that era, some of these were actually quite fun. You wouldn’t want them to spread to your PC, but they’d often do quirky things like make all the letters fall to the bottom of your screen or challenge you to a game of cards to save the contents of your hard drive.

As malware became more serious, the internet and portable media allowed it to spread more freely, and awareness grew. It became common practice to buy an anti-virus product to identify and stop malicious software, and therefore it was only natural that the name “anti-virus” became a casual synonym for all security software, much like any video game console was sometimes referred to as “a Nintendo”.

But the truth is that traditional anti-virus software is quite limited. It relies on hashes and signatures to detect malware, and therefore if the author finds a way to alter their malicious code slightly each time it spreads (polymorphism), it can evade detection. Because it scans for files, standard anti-virus software can also miss attackers’ abuse of legitimate tools, because the files on disk are all benign.

The other limitation of traditional anti-virus software is that it usually only provides a small set of automated remediation actions. If it detects malware, it will at most usually terminate any associated processes and quarantine the files. Any further action requires manual access to the computer.

EDR tools, including CrowdStrike, do a whole lot more than this. While they do scan files and quarantine them (CrowdStrike even has a component called next-gen anti-virus, or NGAV), to call them “anti-virus” is to sell their capabilities seriously short. EDR products essentially monitor everything that happens on a computer and pick through it with a fine-toothed comb for malicious behaviour - even for threats that do not involve files, like in-memory malware or attackers with direct hands-on-keyboard access.

When malicious activity is detected, EDR also gives cyber security professionals many more options to respond to attacks. If it looks like malware could spread between systems, they can disconnect them from the network with a click to contain the incident. They can reverse changes made by threat actors. And if necessary, they can access the system via a remote prompt to check its current state and perform remediation actions. EDR is an invaluable Swiss army knife of response capabilities for defenders.

2. “EDR is corporate spyware”

Imagine you’re tasked with protecting your organisation against cyber criminals, ransomware, and other threats - things that if they went unchecked could severely impact operations, cause irrepairable reputational damage, or cost huge sums of money. Ultimately, you and your colleagues’ jobs could all depend on your success. What’s the best tool your could have in your arsenal to detect malicious activity?

The answer is logs. If you can see exactly which files are written and by whom or what, which processes are run and with which command line arguments, who logged in and where from, and which IP addresses systems are communicating with, you’ll have a huge bank of data to review for signs that something is wrong, and to fully investigate any incidents when they do occur to know exactly what happened.

At an endpoint level, this is exactly what CrowdStrike and other EDR products do. They watch everything that’s going on, review it for malicious activity, and provide responders with detailed log data that they can pick through to determine the full scope of an incident in order to clean up the mess and put in place improved security measures to prevent the same thing from happening again in future.

Cyber security professionals sitting in security operations centres (SOCs) have no interest in whether Bob from accounting is spending too much time on Facebook, and frankly, they don’t have the time to check. They are interested solely in investigating threats to the organisation - perhaps if Bob clicked a phishing link in an email or downloaded malware from a site claiming to offer free software.

In these cases, the logs provided by an EDR tool are invaluable to working out where the threat came from and how much damage it caused. Analysts can use the information within to find any other malicious files on the system and remove them, as well as identifying the exact domain and URL associated with each threat so they can be blocked and other users can’t fall foul of them in future.

I can understand the confusion when there are so many stories about employers watching workers through webcams and monitoring their mouse movements, but that is not the objective of an EDR product. Cyber security is not HR and it’s not some sort of hi-tech productivity monitoring service - it’s there to protect the company from malicious attacks and to contain any incidents that do occur before they can escalate, and it might well have saved your job at some point without you realising it.

3. “EDR isn’t worth the risk”

This is by far the most subjective item on this list, and perhaps the hardest to weigh up. If EDR products like CrowdStrike require such low-level, privileged access, and one slip from a vendor can render a system unusable, is it worth the risk to run the security software in the first place?

I think there are a couple of misconceptions to address for those who would answer “no”. Firstly, despite what many small business leaders might think, your organisation is a target for cyber criminals. We are past the point where only those holding immense wealth or state secrets are attacked. Your business needs your data to operate. Even if the contents of your files are worthless to the threat actors, they know you’re likely to pay up to restore operations if they can manage to deploy ransomware on your network.

Secondly, this stuff isn’t rare - it happens all the time. For the reasons above, cyber criminals do not need to target specific organisations. Instead, they can scan the internet en masse and fire out “spray-and-pray” campaigns, then work with whatever vulnerabilities are found or whichever users bite. If you’re unaware of any attempts to compromise your organisation then you’re either very lucky or you need to go and pat your security team on the back for the work they’re doing in the background to keep things safe.

Then there’s the fallout and human impact of an incident when a threat does get through. Having worked in and around incident response for years, I can tell you that a significant incident can be a very traumatic event. It’s not just not being able to work - it’s not being able to pay employees because the payroll server is encrypted, not knowing if you’ll be able to support your family, and in same cases lives lost.

Cynics will point out that yesterday’s CrowdStrike incident had similar consequences, but I’d encourage you to weigh that against all the times CrowdStrike and other EDR products have prevented similar scenarios - many instances of which you’re unlikely to be aware of. The bug shouldn’t have made it to production and I’m sure security vendors around the world are now taking a cautious look at their development and deployment processes, but in my opinion we should be careful not to let this one very visible slip-up overshadow all the would-be disasters that were quietly stopped behind the scenes.