What a security operations centre (SOC) is and how it works

The security operations centre (SOC) is the heart of a firm’s cyber defences. Here are the basic elements and processes that a SOC uses to monitor for and respond to security incidents.

Cyber security has a staffing problem. With so many roles out there and so few people with the right skills, an increasing number of people with non-security backgrounds like myself are joining the industry. While they’re obviously keen to learn, there are so many areas of cyber security that any initial training they take may mention some facets only in passing.

That’s what happened to me in some respects when I joined the industry from the SANS Cyber Retraining Academy. One area that I was aware of, but without much depth, was the role of the security operations centre (SOC). Now that I’m more familiar with the concepts behind SOCs, I thought it might be handy to put a primer together for other newcomers.

What is a SOC?

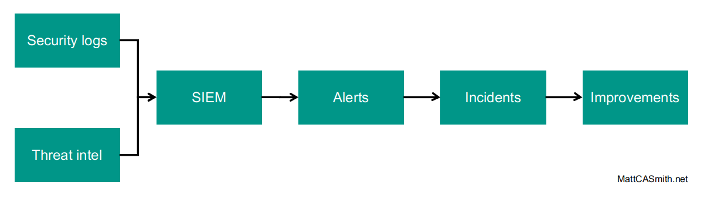

The security operations centre is the heart of a business’s cyber security efforts. It may be situated on-site, or the organisation may prefer to outsource this function to a managed service provider. The primary purpose of a SOC is to take the company’s available security data, use it to identify suspicious events, and respond to these incidents.

The diagram above shows the way a SOC achieves this. There’s more to a SOC than this, of course, but I’m aiming to cover the essentials here. In the rest of this post, I’ll cover the basics of each of the stages that make up this monitoring process.

Security logs

A critical part of monitoring for malicious activity (and one that’s become far more interesting to me than I ever imagined since I joined the industry) is gathering security logs from the business’s various devices and solutions. This includes firewalls, anti-virus solutions, intrusion prevention systems, Active Directory, web proxies, and any other relevant sources.

Log processing is an art form in itself. Each vendor’s products spit out logs in a slightly (or radically) different format, and these must be parsed and regulated into a common format so the events can be combined in a useful way in the security information and event management (SIEM) tool – more on that a little bit later.

Threat intelligence

As well as gathering data from internal sources, businesses can bring in outside data – threat intelligence – to aid their security monitoring. This comes from a variety of sources (e.g. paid feeds from security firms and open-source intelligence) and a multitude of forms (everything from lists of known malicious URLs to reports on vulnerabilities that need to be patched).

Where threat intelligence comes in automation-friendly formats – for example, lists of malicious domains, IPs, hashes, and other indicators of compromise (IOCs) – these can also be fed into the SIEM so they can be matched against data in the organisation’s security logs.

SIEM

The SIEM is where the magic happens. The input data is processed using rules – if a match is detected, an alert is generated for investigation. These rules can cover just about anything, from multiple failed logins by a user account to IPS or anti-virus detections of certain types of malware that the business is particularly concerned about.

The advantage of using a SIEM tool over processing individual logs is that as the events are in a common format they can be correlated with data from other sources. For example, domains recorded by the web proxy can be matched against IOCs from threat intelligence, or firewall logs showing traffic targeting certain IPs can be linked to particular types of malware.

Alerts

But an alert is not necessarily an incident. For all the wonders and efficiencies of an automated SIEM tool, at the end of the day it will alert on any match against your rules, regardless of any mitigating circumstances that a human could quickly pick up on.

This is where the SOC’s Level 1 analysts come in. They take the SIEM’s alerts, which are usually distributed via a ticketing system, and perform basic, process-driven checks to determine whether further action needs to be taken. As this is a fairly straightforward job, it’s often where newcomers to the industry find themselves, and serves as something of a proving ground before they move on to bigger, more stimulating things.

Incidents

Once an incident reaches the Level 2 and 3 analysts, it is likely that it requires a more thorough investigation. Essentially, these analysts will work through the main stages of incident response – analysis, containment, eradication, and recovery – which make up a process that I’ll probably cover in more depth in a future post.

Incident response can involve further, manual log analysis, communication with users and system owners, the containment and rebuilding of endpoints, and other actions. This all depends on the organisation’s priorities and risk appetite and the powers that have been granted to the SOC to take action on security incidents.

Improvements

The final stage of any incident response is to consider the lessons learnt. These could be changes to processes (for example, granting the SOC greater power to act in case of an incident) or technologies (like blocking an IP address connected to a malware detection at the perimeter firewall to stop future command and control traffic).

It should also be considered where the results of an investigation could feed into improvements to the SOC process. IOCs discovered during the investigation can be fed into the SIEM tool, for example, or perhaps an additional log source could be onboarded that would have enabled speedier detection of the incident.

Further reading

As I mentioned at the start of the post, I only intended to provide an overview of the main SOC processes here, but if you want to learn more there are some great resources around:

- Building a World-Class Security Operations Center: A Roadmap (SANS)

- Cyber Security Monitoring and Logging Guide (CREST)

- Boiling the Ocean: Security Operations and Log Analysis (SANS)

If there’s anything you’d add, please let me know in the comments below.

And yes, that’s a still from the old-school Hideo Kojima game Snatcher, and not a photo of an actual SOC taken on a Game Boy Camera. It’s not that far off the truth, though…