Setting up Pi-hole to rein in an extremely noisy Samsung Smart TV

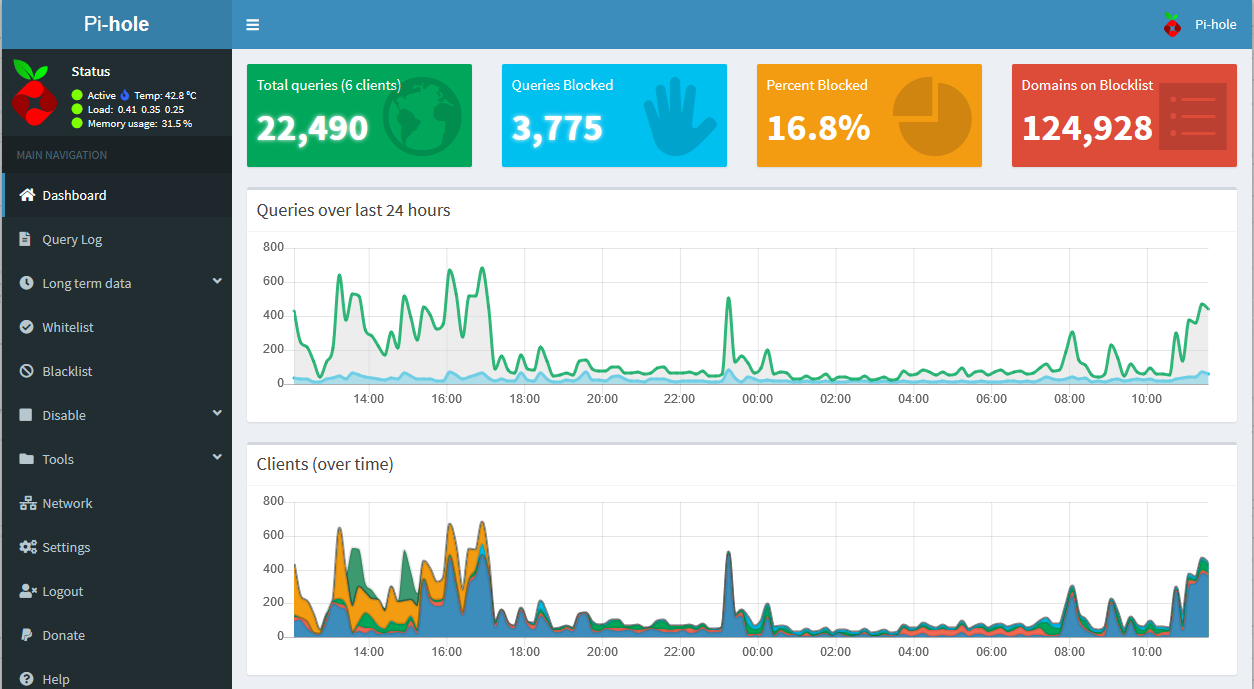

A restless mind, a new feature, and a concerning news story had me worried about privacy over Christmas. Here’s how I installed Pi-hole on my home network to try to block requests from my Samsung Smart TV – and what the data it collected revealed…

It was the night before Christmas – or at least some time in December – and I was browsing through the options on my Samsung Smart TV for something to watch when I noticed a Sony PlayStation advert on the main menu. That was odd, I thought. There was never a banner there before (sigh), and how would Samsung know that I play video games? They had no way of knowing which consoles I owned.

I didn’t think much of it at the time and so didn’t take a photo (the one above was taken a week or two later when the next banner appeared). PlayStation ads do appear during breaks on prime time TV, after all, so it might not have been tailored at all. I only reached the point of taking action a weeks later, when Reddit alerted me to a disturbing-sounding news story about Samsung Smart TVs:

Samsung’s privacy policy reveals an unnerving reality: that Samsung Smart TVs are sending clips of whatever is playing on the television to be sent back to Samsung. It’s hard to imagine a deeper violation of privacy from a smart TV set than having a screenshot of what you’re watching be uploaded to the cloud for corporate advertising purposes…

If you enable Samsung’s Internet-Based Advertising service, your TV viewing history will be siphoned up and sent back to Samsung to be shared with third parties that pay Samsung to send advertising directly to your screen.

Now I want to be completely clear that I cannot vouch for the source and I have absolutely no idea whether my TV was sending clips to Samsung (one of the most popular posts on this blog, in fact, was about eerily relevant adverts that are likely down to clever data science). But the privacy policy concerned me, and however you look at it, retroactively embedding advertising into a product I paid hundreds of pounds for is not cool. So I set out to find a way to put an end to this behaviour…

A black hole for advertisements

Enter Pi-hole – an open-source software package designed to be installed on a Raspberry Pi that can be used to block connections to advertising domains. This can improve the user’s browsing privacy across all devices on the network – even within apps on smartphones and TVs – bolster network security by blocking potential callouts to malware command and control servers, and (in theory, at least) boost internet browsing speeds by saving endpoints the effort of downloading all those banner ads.

So how exactly does this magic box work? Every time you try to connect to a website – let’s say you enter “example.xyz” in Firefox – your computer sends a domain name system (DNS) request asking a DNS server for the IP address corresponding to that domain. If the DNS server replies and tells your computer that example.xyz’s IP address is 1.2.3.4, your computer will then make a connection to 1.2.3.4 and ask for the data that makes up the web page you requested.

Pi-hole sits on your network and acts as the designated DNS server for all your devices. Your router passes all DNS requests to the Pi-hole and it checks the domains against blacklists of advertising and malware domains. If the domain is a match, the DNS request is blocked and never returned. If it checks out, the DNS request is passed to a DNS server on the internet for a response.

So the Pi-hole effectively prevents your computer from knowing where advertising servers are located, meaning banner ads and tracking scripts fail to load. An added benefit for data geeks like me is that it logs all this data and displays it on a neat web interface that acts as a rough approximation of a record of all browsing activity on your home network – interesting for tinkering and analysis, although the data can be anonymised and turned down for the privacy-conscious among us.

Setup and DNS log analysis

Setup was… not smooth. It turned out that my provider’s cheap router (which I’m planning on replacing) doesn’t like setting changes, and more than once it went non-responsive and showed a configuration of lights that internet forums informed me meant it was bricked and would need to be replaced. Luckily they were wrong, and within a few hours I had both a functional router and a Pi-hole ready for action.

I took the extra measure of setting up the Pi-hole as a dynamic host configuration protocol (DHCP) server, making it responsible for handing out IP addresses to devices on my network. This way it can be set to assign static IP addresses and custom names to known devices, making it a lot easier to keep track of which device is responsible for which DNS requests in the Pi-hole’s logs.

The next step was to find out what domains my smart TV was making requests to so I could block them. This might sound like it would require intricate detective work, but it was actually extremely easy, because once I filtered the Pi-hole logs for requests from my TV I could see that it was calling out to several domains, some of them as frequently as every couple of seconds.

samsungcloudsolution.com

samsungrm.net

samsungelectronics.com

The first of those was the main culprit, but there may be more – I’m keeping an eye on it for now and will update my settings accordingly. A quick blacklisting later and my Pi-hole was set to reject any DNS requests for these domains. It was time to switch everything back on and take a look at the results…

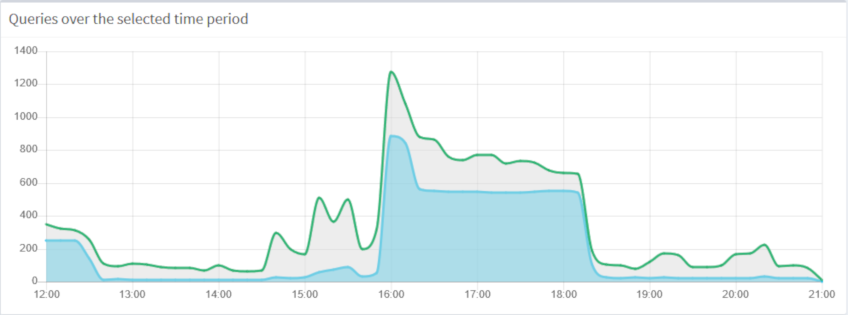

Look at the graph above and guess when I turned on my Samsung Smart TV. It’s not a trick question – after blacklisting the domain names above, the percentage of the total DNS requests on my network that were blocked shot up to more than 50 per cent, including 7,000 during that football match alone!

Project in review

So what is my TV actually doing over all these attempted connections? Is it really taking screen captures of my viewing and sending them back to Samsung for analysis? That’s a question that goes beyond the scope of my project. Even if I allowed the connection and intercepted the packets, it’s likely (hopefully) that their contents would be encrypted and unreadable, so it’s hard to say.

It is likely, however, that these calls out to Samsung’s servers are used for at least some kind of tracking or metrics purposes, because that’s what tech firms do (because they’re full of data geeks like myself). And I can say for certain that they’re non-essential, because since I blocked them the functionality of my smart TV hasn’t been affected at all. Funnily enough, I haven’t seen any more ads, either.

So was this a slightly paranoid exercise? Maybe. But I’d been wanting to experiment with a Pi-hole for a little while, so it gave me an excuse to set one up, and helped me to both learn a little bit more about network behaviour and put what I already knew into practice. The Pi-hole is also a source of some potentially interesting logs – so perhaps look out for some analysis in a future post.